BHASA: THE SANSKRIT DRAMATIST

Contents

- Introduction to Sanskrit Drama

- Discovery of Bhasa’s Plays

- Date of Bhasa

- Plays of Bhasa

- Sources of his Plays

- Features of his writings

- The Problem

Introduction to Sanskrit Drama

In Sanskrit Literature, Sanskrit drama has a special identity. A large number of Sanskrit plays have been written since the 12th century down to the modern times, their plots being generally derived from the Mahabharata and Ramayana. Sanskrit dramas, throws light on the Hindu customs, tradition, rules and regulations. The drama has had a rich and varied development in India, as is shown not only by numerous plays that have been preserved, but the native treatise on poetics which contains elaborate rules for the construction and style of plays. The Sanskrit dramatists show considerable skill in weaving the incidents of the plot and in the portrayal of individual character, but do not show much fertility of invention, commonly borrowing history. In the history of Sanskrit drama, Bhasa is known as the earliest Sanskrit dramatist and many of his complete plays have been found.

Discovery of Bhasa’s Plays

In 1912, the Mahopadhyaya T. Ganpati Shastri came upon 13 Sanskrit plays at Namboothiri Home named Manalikkara Madom (present Kanyakumari district) that were used in the Koodiyattam plays. While touring Kerala searching for Sanskrit manuscript, he came across a palm-leaf codex in Malayalam in a village near Trivandrum. Although they carried no name, he deduced based on internal evidence that they were by the same author and concluded that they were the lost plays of Bhasa.

Date of Bhasa

Bhasa is commonly dated between the 2nd century BCE and 2nd century CE. But the date of Bhasa is one of the most vexed questions in Indian chronology and one is surprised to find a difference of over fourteen hundred years in the earliest and latest dates ascribed to him by different scholars.

- INTERNAL EVIDENCE

- The Udayana plays are handed down from historical traditions, and Udayana, Pradyota, Darisaka are historical personages belonging to the 6th century BC. Thus, 6th century BC is the upper limit for Bhasa’s date.

- The Pratijana, Avimaraka furnish us with historical data. The enumeration of the royal families of North India, traced back to the Maurayan period, shows the poet to be appproximately in the period of Nanda (345-321BCE) or Chandragupta (340-298BC).

- The reference to Sakyasramanaka and Nagna Sramanika, place the poet definitely after the period of Buddha i.e. after the 6th century.

- The sociological conditions portrayed in these works show many parallelisms with the Jatakas and Arthshastra.

- The custom of throwing sand in the endorsers of temples recorded in Pratima Nataka is found only in the work of Apastamba (5th century BC) showing the poet flourished in the period not far removed from Apastamba.

- There are also numerous parallelisms in significant particulars between the social conditions of the Mauryan age and those depicted in the plays, showing the Arthashastra and these plays to be products of the same period. (I.e. is 5th century).

Thus, the cumulative effect of all the factors considered under “Internal Evidence” places the period of the poet between the 5th and the 6th century BC.

- EXTERNAL FACTORS

- Kalidas in the prologue to his Malvikagnimitra refers to Bhasa as an old poet of established renown.

- In the Arthashastra of Kautilya, the 2nd stanza appears in the Pratidnya Yaugandharayana in the same connection as a war song to encourage soldiers. Kautilya probably found the quotation from Bhasa quite appropriate and used it in his work.

Thus, the extended evidence places the 4th century BC as the lower limit. The internal and external evidences, therefore, jointly point to the 5th and 4th century BC as the period of the author.

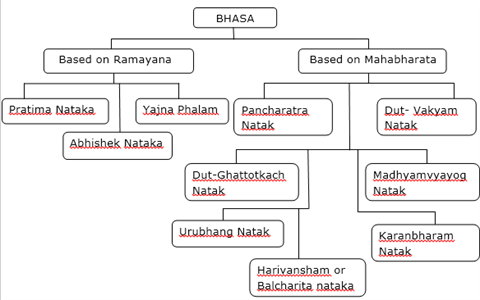

Plays of Bhasa

Bhasa’s other plays are not epic based. Avimaraka is a fairy tale. His most famous plays Pratidnya-Yaugandharayana (the vow of Yaugandharayana) and Swapanvasavadattam (vasavdatta in dream) are based on popular stories that had grown around the legendary king Udayana.

Sources of his Plays

It is seen that the poet is much indebted to the Mahabharata and Ramayana. In all plays, some short episode is taken from the Mahabharata and Ramayana and freely dramatized.

- MADHYAMAVYAYOG: - In Madhyamavyayog, there is a blending of the story of the reunion of Bhima and Hidimba with that of Brahmins. The latter finds its source in the Sunahesepakhyan of the Aitaraya Brahmin, and the former of is the poet’s own creation, the epic supplying him only with characters and atmosphere.

- DUTA-VAKYA: - In the Dutvakya, Krishna the emissary, spoken of in the Mahabharata (Udyogparava) has been dramatized to glorify Krishna and proclaim his identity as Vishnu. Duryodhana is depicted as the real emperor in the drama, whereas Dhrutarashatra was the Emperor in the epic. The scene of divine weapons appearing in human from is a specialty of Bhasa, employed probably to cater to public taste.

- DUTA-GHATOTKACH: - In this drama, the poet is indebted to the epic for characters only, everything else being the fruit of the poet’s imagination and invention.

- KARANABHARAM: - In this drama, the poet mainly follows the epic. The poet has transferred the incident of Karna’s gift of his armour to Indra from the forest to the battlefield in order to heighten the effect, and has ennobled the characters of Karna and Shalya.

- URUBHANGAM :- This drama, dramatized Shalyaparva with slight changes invented by the poet; such as, the secret sign to Bhima comes through Krishna in the play whereas the epic speaks of Arjun as throwing the hint; according to the epic, Balarama was not present at the club fight nor were Dhrutarashatra, Gandhari, Durjaya and the queens of Duryodhana on the battle field. The poet shows Duryodhan on a higher plane.

- PANCHARATRA: - In this drama, three acts have its basis the cattle-rapid; slaughter of Kicakas and the marriage of Abhimanyu with Uttara as told in the epic story and sacrifice of Duryodhan, his promise to grant half kingdom to Pandavas and their news of coming within five nights given to Drona, Abhimanyu’s siding with Duryodhana, the scene with Bhima. Abhimanyu’s and Brahannala are among main scenes or incidents introduced by poet.

- BALCHARITA: - The drama, widely differs in detail from the stories of Krishna in the Balcharita (Harivansham). The poet’s source probably was an earlier version of the Krishna story on which the Harivansha and Puranas are based. The Balcharita presents, in common with the Dutvakya, the Divine weapons in human form.

- PRATIMA:- The poet is indebted to the II and III book of Ramayana, but he builds a supernatural repertoire of his own. The introduction of the Valka incident, the statue houses, the changed genealogy of Rama, the abduction of Sita by bringing Rama and Ravana together and making the golden deer necessary for the sraddha, and the absence of Lakshmana at the time, and Rama’s coronation in the grove are the main departures of the poet from the epic. The characters of Rama, Sita, Dasharatha, Bharata, Kaikayi and sumantra are portrayed in a favorable and on a higher level.

- ABHISHEKA:-This drama, deals with the epic story as given in the IV, V, VI books of the Ramayana which the poet follows very closely. The manner in which the waters of the ocean divide to offer passage to the lord is the poet’s own invention reminiscent of the similar device in the Balcharita.

- AVIMARAKA :- As regards the source of this play, they have variously been stated to be folklore, poetic invention, Katha literature or the story of the spirit of monsoon destroying the demon of drought. A comparison of the stories as given in the Kathasaritasagara, Jayamangala Tika, a Buddhist Jataka and Avimark shows that the Jayamangala follows the Avimark in some respects. It appears that the Jataka story must have been current among the people at that time of Bhasa and he probably used it as the main story. The supernatural element of the ring incident has been added to the story by the poet for popular appeal.

- SVAPANAVASAVADATTA AND PRATIDNYAYAUGANDHARYANA:- These two are most famous plays of Bhasa. Svapanavasavadatta (Vasavadatta in the dream) and Pratidnyayaugandharayana (the vow of Yaugandharayana) are based on the legends that had grown around the legendary king Udayana. The 1st play tells the story of how king Udayana married princess Vasavadatta. The next play tells how king Udayana, with the help of his loyal minister Yaugandharayana, later married the princess Padamavati.

Features of his writings

- CHARACTERIZATION BY BHASA IN HIS PLAYS: There is not only a large number of characters but a very wide range and variety to be found in Bhasa. With all this, however, there is always the tendency to avoid adding needless characters on the stage, like the omission of Kashiraj and Suctsena in Avimaraka. Bhasa portrays men and women of this world as they are. In contrast to the general trend in Sanskrit drama to paint types and not individuals, Bhasa is found to have portrayed living men and women, which he has drawn from all grades of society from the highest class to the lowest. The characters never talk unnecessarily. They live a plain, straight forward life, most of the characters make for a good psychological study. Bhasa displays his skills at characterization in the legendary plays and romances.

- In his hands, the Vidushaka is seen without his gluttony which came to be associated with him in later dramas and has become a constant companion and a helpmate of the hero.

- Padmavati and Vasavadatta set an example to co-wives by their sisterly regard for each other and sacrifice for their husband. Though required to marry again for political reasons, Udayana still cherishes sweet memories of his wife.

- Yaugandharaya is a clever, faithful, and devoted minister, well versed in strategy and more than a match for his rival.

- Vasanttasena is shown as an ideal courtesan, full of love and devotion to Charudatta, who is portrayed as an ideal thoroughbred man of the town.

- The love between Avimarak and Kurangi is not a mere vagary of the flesh but constant and everlasting.The characters of Bhasa thus, are simple, human and extremely life-like. They are not as romantic and imaginative like Kalidasa and Bana, not as poetic and sentimental as those of Bhavabhuti, not so vigorous as those of Bhattanarayan, not so fickle and fairylike as those of Harisena and not so humorous and realistic as those of Shudraka.

2. SENTIMENTS IN HIS PLAYS:- The main aim of Sanskrit drama was, as already stated, to convey a moral by evoking a particular sentiment in the minds of the audience and thus lead them to the plot, characterization etc. occupying a subsidiary place in the scene. Bhasa does not employ the premier sentiments of Shringar to any appreciable extent and his works serve as the best illustration of the futility of the dictum that a drama cannot be shown its best without Shringara as the dominant sentiment. Bhasa is fond of Karuna or Pathetic sentiment also. It is seen in the wailings of Dhritrashtra, Gandhari and Dushala in the Dutghatottkach. The lamentation of Devaki in the Balcharita and Dasharatha in Pratima. The sorrow of Duryodhan in Urubhanga, the pathetic conditions of Avimarak and Kurangi during their separation in the Avimaraka, of Vasavadatta in the Svapna and of Sita in Abhishek. Karna’s state in Karnabharam and Ravana’s grief at Indrajit’s death in the Abheshek also serve as illustration of Karuna Rasa. Next is Rudra or the sentiment of Fury, which is found in Bhima’s encounter with Gatottkach in the Madhyamvyayog. The visions of Kansa in the Balcharita bordering explosion, Balrama’s anger against Bhima at his unfair fight with Duryodhana in the Urubhanga; Bharata’s disowning his mother in the Pratima are a few examples. Next is Vira or the Heroic sentiment which is the speciality of Bhasa. Vira has been subdivided into Yuddha (courage), Dharma (virtue), Daya (compassion). Yuddha Vira is exhibited in the battle of Rama and Ravana, Duryodhana and Bhima, Uttara and Kuru army. Duryodhana in the Pancharatra in parting with half his kingdom to the Pandavas in pursuance of his promise to Drona exemplifies the Dharma Vira. Karna’s offer of his armour to Indra in the Karnabharam is an illustration of Daya Vira. Bhayanaka or the sentiment of Terror is found in the Madhyamavyayog when the Brahmin family finds itself suddenly confronted by a demon; in the scene after Indrajita’s death in the Abhisheka; in the description of the battle field in the Urubhanga; in the killing of Kansa by pulling him by his hair in the Balcharita.

Next is Adbhuta or Wonder which has been exhibited in a number of these plays. It is found in the appearance in human form of divine weapons in the Dutvakya and Balcharita, in the scene of the magic ring given by Vidyadhar to Avimaraka, in the appearance of Varuna and Agni in Abhishek. Vatsala, seen in the love of Bhima for Ghatottkacha in the Madhyamavyayog, of Arjuna and Bhima for Abhimanyu in the Pancharatra. The love of the jester-companions for Charudatta, Avimarak and Udayana may also be included in this category. Next is Hasya or the comic sentiment. There are numerous instances of Hasya in the work of Bhasa. Santusta in the Avimarak and Sakara in Charudatta supply us with comic relief in the numerous situations in which they figure. The Vidushakas in Svapanavasavdatta and in Charudatta also create some funny moments.

- STYLE AND DIALOGUE: The influence of the epic is responsible for simplicity and directness of style. The sentences are replete with the wealth of ideas beautifully expressed. The language is very simple, natural and touching, alternated with beautiful figure of speech, though there is the use of alliteration at some places. The style is flowing and direct; the verbal flow is limpid. We find in Bhasa an adequate and forcible expression of strong emotion. He is the master of silence. There is change in style as befits the occasion and sentiment as directed in Natyashastra. The dialogue is a necessary element of drama, and Bhasa is a master of Conversationalism. His dialogues are crisp and intensely dramatic. The speeches of the characters are natural, realistic, vigorous and direct. These dramas give the impression that Sanskrit was the living language of that time. Verses are successfully employed in dialogue. A stanza is occasionally split up in parts and each is taken by different characters.

- BHASA AND TRAGEDY:- It is said that absence of any effort at tragedy is a striking characteristic of Sanskrit drama, but the discovery of Bhasa’s plays has brought about atleast one real tragedy in Urubhanga. The Urubhang is a tragedy viewed from the point of Aristotle and Hegel. Urubhanga is a real tragedy, as in Bhasa’s view, Duryodhana is a hero, a noble king, not an evil man. Throughout in the Urubhanga, Duryodhana receives our sympathies, and he is not at all depicted as the enemy of Krishna and there is absolutely no feeling that he was served right.

- DESCRIPTION AND NARRATIONS: Predilection for certain descriptions has been observed as a common characteristic of these plays. Bhasa is a close observer of nature and his description of natural phenomena is interesting, realistic and vivid. He gives diverse details and various facts connected with the phenomenon that he portrays. Bhasa is fond of planting pithy proverbial phrases in his plays, following are the famous phrases of Bhasa

- भाग्यक्रमेण हि धनानि पुनर्भवन्ति A

(Charudatta)

- “Rupen striyah kathyante parakramen tu purushah” (Panchartra)

- The Problem: The discovery and publication of the 13 plays ascribed to Bhasa in Trivandrum will go down as the most epoch-making landmark moment in the history of Sanskrit drama. Much has been written in support as well against the Bhasa story. Opinion is yet sharply divided, and nothing like a definite conclusion is reached even after many years of heated controversy. Although the name of Bhasa is nowhere mentioned in the manuscript, neither in the body of the text nor in the colophons, T.Ganapatishastri came to the conclusion that all these dramas are to be ascribed to Bhasa principally on the following important ground.

All these dramas begin with the state direction नान्द्यन्ते ततः प्रविशति where as in the classical dramas we are accustomed to, have the Nandi first and then the stage direction etc. This technical peculiarity of the Bhasa plays seems to be alluded to in the famous stanza of Balcharita, where Bana tell us that the dramas of Bhasa begin with the appearance of the Sutradhara and are rich in persons and episode. The prologue is called Sthapana everywhere in place of prasthavana. Unlike the classical dramas the title of the work and the name of the author are not mentioned in the Stapanas in these plays, which fact reinforces that the plays belong to pre-classical times when details such as these were possibly left to the preliminaries. The Bhratavakya ends everywhere with the prayer, “may our mighty king rule the whole earth”. The structural dramas further present a structural similarity, and the opening verse of the plays string together the principle characters by what is technically called the Mudralankara.

One of the plays is mentioned by RAJSHEKARA in Kavyamimamsa (880-920 AD) with the name of the author; therefore, it stands to reason that the rest of the group which show numerous affinities with it as regards style, stage-techniques, ideas and vocabulary should be ascribed to the same poet of Svapanavasavadatta. In support of this thesis, there is further evidence of the matter, especially the preponderance of the Epic shloka, while the deviations from Panini’s grammar and peculiarities of these Prakrita unmistakably prove that the plays are pre-classical. On the other hand, the opponents of the theory have raised objections and they have succeeded in showing that the plays in question are of doubtful authenticity and of uncertain date. They explain the omission of the title of the work and the name of the author on the ground that the play was obviously meant to remain anonymous. As to the verse from the Balcharita which states that the dramas of Bhasa were begun by Sutradhara, this innocuous statement by itself could not reveal any distinguishing features of the dramas of Bhasa; in fact the poet is merely trying to avail himself of an ingenious equivoque to find same balance between objects which have obviously nothing common between them. As a matter of fact even the classical plays can very well be described as begun by the Sutradhara; the position of the 1st verse is a peculiarity of South Indian manuscripts and not the characteristic of pre-classical period. The Prakta of the drama is a factor depending more on the provenance and the age of manuscripts than on the provenance and the age of dramatist.

From the foregoing summary of arguments on both side, it will be seen that none of the arguments advanced is absolutely convincing and therefore, there have been from the very beginning, critics who were skeptical about the authenticity of the plays who held that these plays, at least some of them bear the evident marks of being abridged versions of probably the original dramas of Bhasa.